[Photographs: Vicky Wasik]

One of my friends in college—we’ll call him “Josh,” because that’s his real name—had a funny way of throwing away bacon grease. He rented the second floor of a two-family home, the sole adornment of the intersection of two small but dangerous county roads, and each of the windows on the second floor looked out on a kind of eave that ran the length of one side of the house, with a runnel at its edge for rainwater. Whenever he finished cooking up a batch of bacon, he’d walk over to a window that looked over the eave and just dump the grease out.

The first time I saw this, I think I was too shocked to say anything. But every time thereafter, I’d say (or shout, really), “Josh! Why are you throwing bacon grease out the window?” And he’d always yell back the same thing: “Do you want me to pour it down the drain?”

Of course, Josh, in his odd way, was right. You should never, ever pour grease of any kind down the drain in your home. But, of course, Josh, in his odd way, was also totally wrong. Unless you’re defending a besieged castle from an invading army, you should never, ever pour grease out your window, either. Don’t be like Josh. Let’s talk about how to dispose of grease properly.

Why You Shouldn’t Put Cooking Oil Down the Drain

You must have seen the news reports and the public-health campaigns, warning of the monster that lies underneath many cities’ streets, growing steadily in their sewers day by day. It goes by many names—”gross,” “disgusting,” “really gross,” “I’d rather not think about it,” “super freaking gnarly”—but it is commonly known as a fatberg, a massive agglomeration of nonbiodegradable waste combined with fats and oils.

The science of the fatberg is far from settled, but the working theory is that cooking fats in the sewer system undergo a process called saponification, which basically means the free fatty acids in sewer water react with alkaline salts to produce a solid substance that is essentially soap. The fatberg soap comes together on a scaffolding made up of wet wipes, which, no matter what manufacturers say, should not be flushed down your toilet.

If you, like me, have ever let that last itty-bitty bit of your soap bar just kind of sit on your shower drain, figuring that eventually it will dissolve and be washed away, only to remain disappointed for weeks until you throw the dang thing out, then you’ll have some idea of how whale-size pieces of soap might mess with a sewer system.

Of course, the fatberg is a city-scale problem that has city-scale origins, and you might think that the quarter cup of bacon fat you’ve poured down your sink can hardly make a difference compared with the output from commercial kitchens and industrial manufacturers. Still, there’s another, more personal reason to avoid tossing fry oil down the drain: Cooking fats will also mess up your own drains, potentially creating clogs that only an expensive call to the plumber can fix.

How to Save Cooking Oil and Grease for Reuse

So, you’ve cooked something—a steak, a duck breast, a flock of chicken thighs, a mess of karaage—and you’ve got a lot of used grease on your hands and in your skillet. What should you do?

The first thing to consider is whether the grease is reusable, and whether you want to reuse it if so. Different cooks have different tolerances for the amount of effort they’re willing to expend to save a few bucks, but I personally save as much reusable fat as possible.

Oil for deep-frying should definitely, definitely be reused. Kenji wrote an article some years back on how many times you can reuse fry oil, how to tell when it’s spent, and how to clean it, so I recommend checking that out first thing.

For other cooking fats, use your best judgment. You need to take into account two things: how hot the oil got during cooking, and whether you have some plan for the saved oil.

The first is the most important, since overheating oil is the surest way to make it unfit for further use. If you’ve used oil for searing, you’ll want to toss it, since it will have started to break down. On the other hand, if your oil was used to make a batch of fried shallots, hold on to it! That now-aromatic oil can be a great addition to vinaigrette, or get emulsified into a homemade mayonnaise.

Or maybe you’ve used a little vegetable oil to brown chicken thighs or duck legs, both to get good color on the skin and to create a nice fond for a sauce or the base of a braise. The grease left in the pan—from both the cooking oil and the rendered poultry fat—is not only fine to save for later (if you’re not using it right away in the recipe, for cooking mirepoix or the like) but is also infused with flavor. I do this to amass a sufficient amount of flavorful fat when I want to make aroma oils for ramen and other noodle soups.

With duck breast and bacon, when cooked correctly—that is, never at extremely high temperatures, and not burned—all the fat that renders out can be saved and put to some future, delicious use. Duck fat–fried potatoes, maybe?

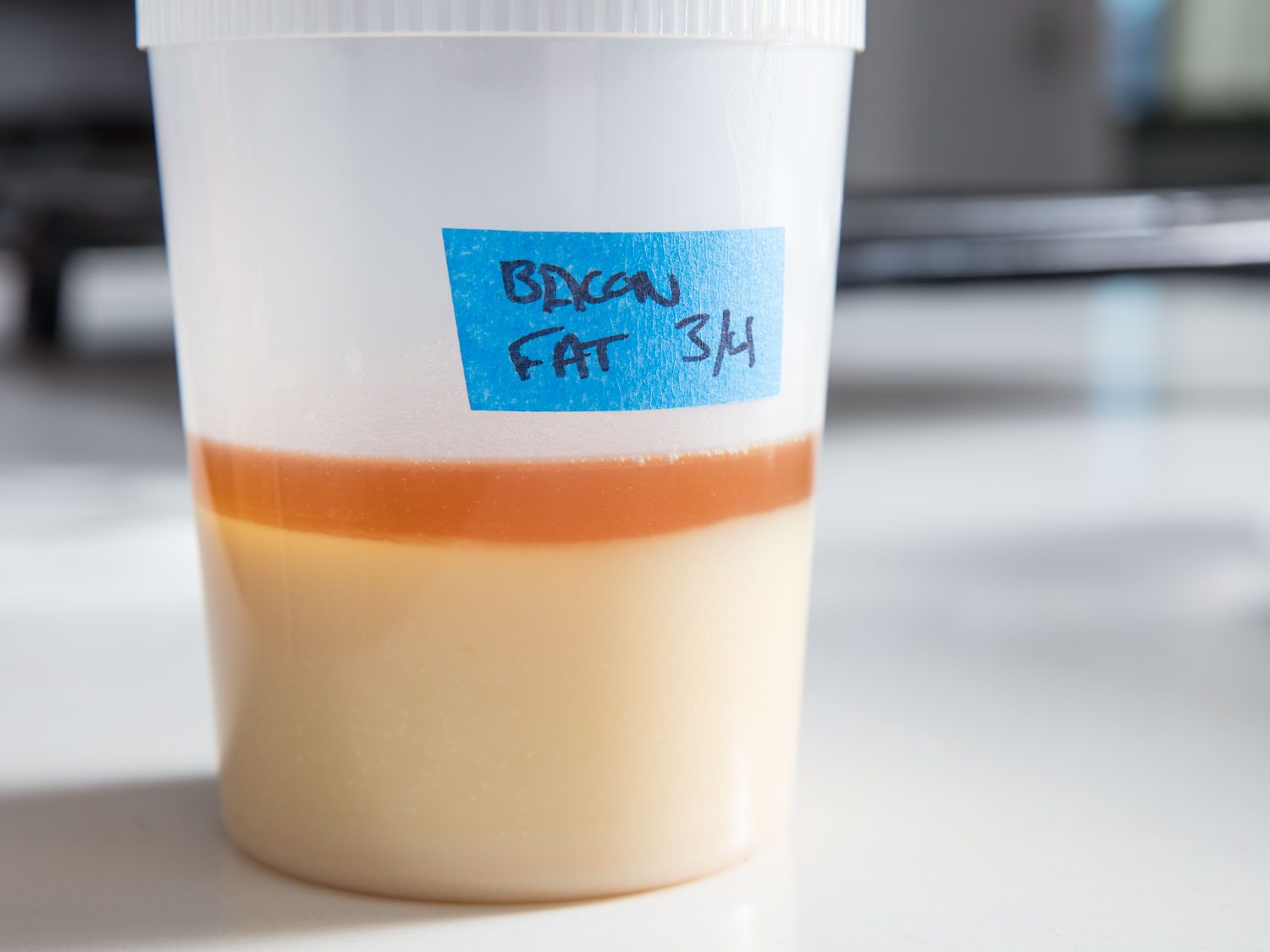

No matter what fat you’re saving, the process is the same: After allowing it to cool slightly (but not so much that it starts to solidify), remove any particulate matter in the oil by straining it through a fine-mesh strainer into a heatproof container. If it’s particularly gritty or dirty, line your strainer with a layer of cheesecloth or a coffee filter.

You can also use the nifty trick of adding a gelatin solution to the liquid fat to clarify it. This method is more useful for the large quantities of oil used in deep-frying, rather than the small amounts of cooking fat involved in browning.

How to Throw Away Cooking Oil and Grease

If you want to dispose of spent cooking grease, the best way to do it is to pour the fat into a sealable container that you’re fine with throwing away. I typically hold on to the plastic bottles in which many cooking oils are packaged, specifically for this purpose. Pour the oil into the container, screw the cap on tight, and toss it in the trash.

If you’re using a plastic deli container, it’s a good idea to tightly wrap the container in plastic wrap before throwing it out, as oil seems to find a way to leak out from under deli-container lids. (Unfortunately, properly disposing of household cooking oil is not very environmentally friendly.)

Some large-scale food operations, like restaurants or college dining halls, participate in oil-recycling programs, in which drums are filled up with spent fryer oil, then picked up by waste-management companies and used for making biodiesel. If you’re chummy with any business owners that participate in this kind of program, it can’t hurt to ask if you can use their oil Dumpster from time to time. Whatever you do, just don’t feed the fatberg monster.

This post may contain links to Amazon or other partners; your purchases via these links can benefit Serious Eats. Read more about our affiliate linking policy.

Source link